Chippenham Our History: Not ‘The’ History, But ‘A’ History

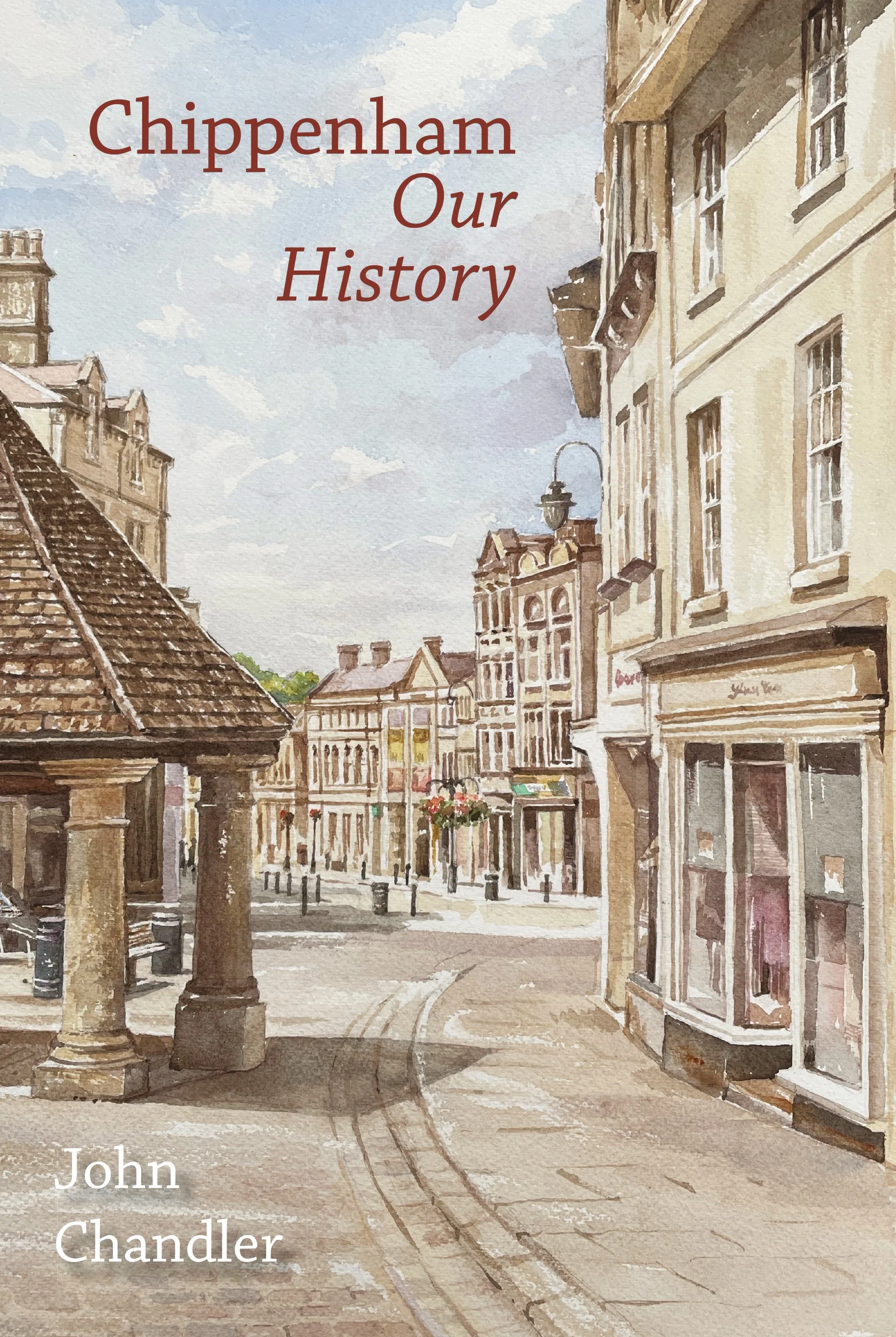

Cover of Chippenham Our History from a painting by John Harris

For as long as I have been researching Wiltshire, whenever I have wanted to find out anything about Chippenham I have turned to Joseph Chamberlain’s Chippenham: some notes on its history, which was published in 1976. Compared with many of the town histories that we use, it seems quite modern, though in fact it is now fifty years old. Chamberlain, from the outset, is quite clear: ‘This is not a history of Chippenham . . .’ and he was not being falsely modest. He was a proper historian, and he knew the difference between writing a history and compiling a list of historical information. His ‘notes’ on Chippenham, it seems to me, are accurate, reliable, and well informed, and he stands high in my estimation. But he is correct – his is not a history of Chippenham. The difference, to suggest an analogy that I have sometimes used before, is between shopping for the right ingredients and cooking the meal; or between selecting the bricks and building the house.

If we extend the analogy to our own work, the VCH researchers are shoppers on a gargantuan scale, filling a whole larder of ingredients, from which present and future historians can concoct whatever meals they choose. And in a sense the red book shortly to appear, like Chamberlain’s, ‘Notes on the history’, is not a history in itself, but an enormous collection of facts. My privilege, commissioned and encouraged by Chippenham Town Council, has been to be the first to quarry those notes so as to attempt to write a short history of Chippenham. But notice that I said ‘a history’ not ‘the history’. The local historian’s craft is to use the evidence, the ‘notes’ at their disposal, to construct as best they can a coherent and faithful explanation of what has happened and how they believe it has affected the place that they are tasked to describe. But my resulting history will be subjective to a certain extent, because it depends on what I think is significant and of interest to my readers. So it is one person’s version of history. And there will be (I hope) many other histories in the future, nuancing the ingredients in various ways to suit the circumstances of their time. History is not about the past – it is about the past meeting the present (and the restless present constantly changes).

So, in writing and illustrating Chippenham Our History, which is to be published on 12 March to usher in a year of community historical celebrations, I have tried to distil into six quite short chapters or essays the town’s history, in a way that local people who would not claim to be historians will find engaging. I have taken my lead from the books that Louise Ryland-Epton has produced about the neighbouring villages, and my effort will appear very similar in style to hers (same page design, cover illustration by the same artist) . But whereas she has seasoned her narratives with case studies on particular topics, I thought that I would round off my history by taking my readers on a stroll through the town and its suburbs, stopping every now and then to look at things that piqued my interest. That is how it appears on the page, but what (subversively) I am really doing is trying to convey the kinds of questions and research agendas that interest local and social historians nationally, and applying them to Chippenham. My hope is that, by sharing my enthusiasms, my readers will see their town in a new light, and set off on their own quests into its history.

Appreciating the places where we live is not just a hobby for historically-minded eccentrics (like me). It may seem fairly innocuous and inconsequential, but local history can be a very powerful and effective way of bonding our communities together, so that we begin to share an appreciation for and cherish those everyday streets and insignificant landmarks that we all tend to take for granted. Chippenham’s history is its identity – celebrate it!

John Chandler